Hanslick’s Historical Relevance

Alexander Wilfing, 2023

Eduard Hanslick is known to many people today primarily as a music critic, as a friend of Brahms and an enemy of Wagner, on the whole as “il Bismarck della critica musicale,” as whom—as Hanslick himself reports in his autobiography Aus meinem Leben (From my Life)—he was dubbed by none other than Guiseppe Verdi, whose Falstaff would later be the subject of Hanslick’s final review (Neue Freie Presse, April 7, 1904). To the opera and concert audience of today, Hanslick is a household name as a constant feature of program guides, more often than not assuming the role of the reactionary who had been overtaken by historical developments. Hanslick’s opposition to Wagner’s late operas, Liszt’s symphonic poems, and the subsequent offshoots of the so-called New German School in particular, as well as his lack of understanding of composers like Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler—whom he candidly admired as a conductor—have nourished this reputation. Thus, it is not at all surprising that he is also prominently represented in Nicholas Slonimsky’s Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on Composers since Beethoven’s Time (1953, reprinted 2000) and is repeatedly identified with the stage figure of Beckmesser, as illustrated succinctly by Norbert Tschulik’s collection Also sprach Beckmesser: Aus den Schriften von Eduard Hanslick (Thus spoke Beckmesser: From the writings of Eduard Hanslick; 1965). The fact that Hanslick’s writings continue to be cited all the same is due not only to their content but for the most part to the critic’s refined writing style and his (often all too) sharp tongue, which makes reading his texts seem worthwhile even after this many a year. There are refreshingly sardonic passages, such as his praise for Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, which as a “memorable artistic experience,” and despite its “interesting musical exceptions or symptoms of illness,” seems to Hanslick “more significant and lastingly stimulating than a dozen garden-variety operas by those numerous healthy composers to whom one pays half too much honor by calling them half-talents” (Neue Freie Presse, June 26, 1868), alongside questionable remarks such as the (in)famous reflection on the occasion of Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto “whether there could not also be pieces of music that one hears stink” (Neue Freie Presse, December 24, 1881).

Eduard Hanslick, photograph by Ludwig Grillich (1892); by courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Eduard Hanslick, photograph by Ludwig Grillich (1892); by courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Hanslick’s review of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Dwight’s Journal of Music, August 1, 1868

Hanslick’s review of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Dwight’s Journal of Music, August 1, 1868

Whatever one may think of these statements, Hanslick’s prominence as presumably the most important music critic of his era is likely due to such provocative positions as well as his profile as an (or the) opponent of the New German School. His reputation as a consistently conservative music critic, a “stodgy, pedantic spokesperson for ‘conservative’ musical causes,” as Dana Gooley—“Hanslick and the Institution of Criticism,” Journal of Musicology 28, no. 3 (2011), 289—encapsulates a widespread stereotype, is, however, clearly exaggerated: Although Hanslick certainly regarded the motivic-thematic work of Brahms and Beethoven as the ideal of music and considered Wagner’s “infinite melody”—which he in later editions labeled as “formlessness elevated to a principle” and a “sung and fiddled opium high” (editions 4–10, V2.6; Eduard Hanslick’s ‘On the Musically Beautiful’: A New Translation, trans. by Lee Rothfarb and Christoph Landerer, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018, lxxxi)—an aberration, he could also warm to more modern composers like Antonin Dvořák, Edvard Grieg, and Bedřich Smetana. His reach was accordingly not limited to Vienna, Austria, and the German-speaking world, but already attained international proportions during his own lifetime. The Journal of Music, edited by the Boston critic John Sullivan Dwight (1813–1893), which appeared between 1852 and 1881 with financial support from the Harvard Musical Association, is particularly representative. Dwight, who shared and occasionally surpassed Hanslick’s classicist conviction, translated a range of Hanslick’s reviews into English, so that between 1866 and 1881 more than three dozen of his essays reached a Boston audience. Hanslick’s reputation was also nourished by his participation in international musical events and in-depth travel reports from, among other places, Bayreuth, London, Paris, and the United States, which he visited in 1890 (see, for example, his reports in Neue Freie Presse, June 24, June 25, and July 29). These extensive musico-critical activities ultimately resulted in Hanslick sitting on renowned music juries—this way, for example, he procured state grants for Dvořák between 1874 and 1877— and repeatedly attending international exhibitions as a correspondent and later as an Austrian delegate, for example at the World’s Fairs in London (1862), Paris (1867), and Vienna (1873).

While Hanslick’s prominence among the musical public is closely linked to his critiques and the figure of Wagner, his continued importance in philosophy and musicology depends on other aspects of his work: In 1856, Hanslick was appointed lecturer for the “History and Aesthetics of Musical Art,” the earliest such position not only in Vienna but rather in the entire German-speaking world. Although music history had been taught at universities since the eighteenth century, until then the activity was for the most part tantamount to the post of a practical music director. The theoretically oriented lectureship of Hanslick, who was appointed associate professor in 1861 and full professor in 1870, was a novelty that is now considered the first professorship of musicology, which has been generally known under that name only since the founding of the Vierteljahrsschrift für Musikwissenschaft (Musicology Quarterly; 1885). (On the history of the discipline in Vienna, see this link.) In 1869, Hanslick published volume 1 of Geschichte des Concertwesens in Wien (History of the Vienna concert scene), which could be considered a pioneering achievement in the sociology of music, as his only historical work in a narrow sense. Later books are composed primarily of collected reviews, reports, and essays that Hanslick wanted to be understood as a living history of music in Vienna and as “aesthetic statistics of opera” (Die Moderne Oper, 1:vi). In Music, Criticism, and the Challenge of History (Oxford University Press 2008, chap. 2), Kevin Karnes frames this approach with reference to Dilthey, Droysen, and Burckhardt as an early attempt at particularistic historiography, which, however, did not prevail historically against philological musicology as developed by Friedrich Chrysander, Otto Jahn, and Philipp Spitta, among others. Even if Hanslick’s relevance for the genesis of academic musicology is for the most part underestimated, his importance as a founder of the discipline nevertheless clearly falls short of that of his successor Guido Adler, who established the Department of Musicology in Vienna in 1901 and shaped the methodology of the discipline for many years with his 1885 essay “Umfang, Methode und Ziel der Musikwissenschaft” (translated as “Scope, Method, and Aim of Musicology”).

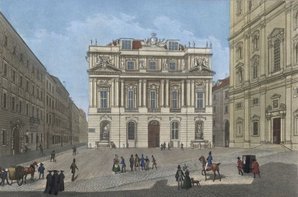

The former venue of the University of Vienna, ca. 1850; by courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

The former venue of the University of Vienna, ca. 1850; by courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Cover of Eduard Hanslick’s treatise Vom Musikalisch-Schönen, 1st edition, 1854

Cover of Eduard Hanslick’s treatise Vom Musikalisch-Schönen, 1st edition, 1854

In addition to Hanslick’s roles as a music critic and professor of the “History and Aesthetics of Musical Art,” his name remains closely associated with a book he wrote at the age of only 29: Vom Musikalisch-Schönen: Ein Beitrag zur Revision der Aesthetik der Tonkunst or On the Musically Beautiful: A Contribution to the Revision of the Aesthetics of Music. This book, which went through ten revised editions during Hanslick’s lifetime (see the index of Eduard Hanslick’s writings below), can be characterized without exaggeration as the most impactful musico-aesthetic treatise of the nineteenth century, whose central assertions continue to inform debates in aesthetics. Vom Musikalisch-Schönen (VMS for short) develops a perspective specifically derived from the intrinsic properties of musical material, whose focus on the object, critical stance against metaphysical speculation, and up-to-date definition of the problem of music and emotion—reminiscent of the twentieth-century cognitivist concept of emotion—remain relevant to contemporary discourse. Historically speaking, particular importance was attributed to Hanslick’s much-cited rejection of the “rotten aesthetics of feeling”—a phrase found only in the preface to the first edition (V1.4)—which, like the analogy between the content of music and the moving arabesque, as well as the notorious catchphrase “the content of music is sonically moved forms” (editions 4–10, 3.6; Rothfarb and Landerer, On the Musically Beautiful, 41), shape Hanslick's reception to the present day. Here, too, the radiance of Hanslick’s treatise, which its translator Geoffrey Payzant, for example, deemed the “founding document of musical aesthetics as we know it” (Hanslick on the Musically Beautiful: Sixteen Lectures on the Musical Aesthetics of Eduard Hanslick, Christchurch: Cybereditions 2002, 17), rapidly outgrew German-language discourse. The reputation of VMS as a pamphlet directed primarily against Richard Wagner—a reputation undoubtably encouraged in the prefaces of later editions (as was already evident from Hanslick’s polemic against Wagner’s “infinite melody”) and certainly not detrimental to the popularity of this book—clearly falls short, however, and also does not do full justice to Hanslick’s impact.

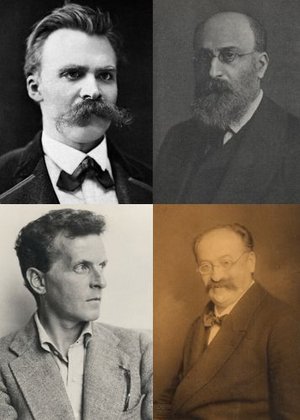

The reception of Hanslick’s writings markedly goes beyond his own epoch and, with regard to music philosophy and musicology, encompasses such central figures as Guido Adler, Friedrich Nietzsche, Heinrich Schenker, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Generally speaking, the impact of VMS, which stretches from the beginnings of academic music research to numerous composers (Pfitzner, Schoenberg, Stravinsky) and established philosophers like Theodor W. Adorno, Karl Popper, and Roman Ingarden, has hardly been researched systematically up to this point. Corresponding research literature is mostly limited to passing references regarding certain analogies between Hanslick and later authors, which often remain vague and do not seriously examine reception-historical correlations. There are notable parallels between Hanslick’s treatise and the late philosophy of Wittgenstein, for example, who determined the meaning of a piece of music to be specifically musical and decidedly rejected the idea that music could be successfully verbalized. While these contexts have hardly been explored, Nietzsche’s relationship with Hanslick, from his Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music, 1872) to his late works—Der Fall Wagner (The Case of Wagner, 1888); Nietzsche contra Wagner (1889), which taks a reserved approach to Wagner—has often been the subject of research. Furthermore, VMS fell on particularly fertile ground with modern analytical philosophy of music and its focus on the relationship between emotion and music as well as its distinctly objective orientation. Although Hanslick already played a major role in the context of Susanne K. Langer’s Philosophy in a New Key (1942), VMS moved to the center of the debate around the 1980s. This development depends primarily on the relevance of the cognitivist concept of emotion in analytical discourse on music, which is laid out explicitly in VMS and attracted the attention of contemporary philosophers such as Malcolm Budd, Peter Kivy, and Stephen Davies. (A detailed analysis of Hanslick’s reception in the English-speaking world can be found under this link). Although no modern aesthetic theorist is in complete agreement with Hanslick’s position, his framing of issues like the relation of music to affect states (feelings, emotions, moods, etc.), the autonomy of the “work of art,” or the aesthetic significance of musical facture, among others, has had lasting impact and continues to influence related debates to this day.

Collage of images of Adler, Nietzsche, Schenker, and Wittgenstein (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

Collage of images of Adler, Nietzsche, Schenker, and Wittgenstein (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

Eduard Hanslick’s Writings

- “Ueber den subjektiven Eindruck der Musik und seine Stellung in der Aesthetik,” Oesterreichische Blätter für Literatur und Kunst 30 (1853): 177–178; 31 (1853): 181–182; 33 (1853): 193–195.

- “Die Tonkunst in ihren Beziehungen zur Natur,” Oesterreichische Blätter für Literatur und Kunst 11 (1854): 78–80.

- Vom Musikalisch-Schönen: Ein Beitrag zur Revision der Aesthetik der

Tonkunst, Leipzig: Rudolph Weigel, 1854. Further

editions:

- 2nd edition, Leipzig: Rudolph Weigel, 1858.

- 3rd edition, Leipzig: Rudolph Weigel, 1865.

- 4th edition, Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1874.

- 5th edition, Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1876.

- 6th edition, Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1881.

- 7th edition, Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1885.

- 8th edition, Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1891.

- 9th edition, Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1896.

- 10th edition, Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1902.

- Geschichte des Concertwesens in Wien, Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1869.

- Geschichte des Concertwesens in Wien, vol. 2, Aus dem Concertsaal: Kritiken und Schilderungen aus den letzten 20 Jahren des Wiener Musiklebens nebst einem Anhang, Musikalische Reisebriefe aus England, Frankreich und der Schweiz, Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1870.

- Die moderne Oper: Kritiken und Studien, Berlin: A. Hofmann, 1875.

- Musikalische Stationen: Neue Folge der “Modernen Oper,” Berlin: A. Hofmann, 1880.

- Aus dem Opernleben der Gegenwart: Der “Modernen Oper” III. Theil; Neue Kritiken und Studien, Berlin: A. Hofmann, 1884.

- Suite: Aufsätze über Musik und Musiker, Vienna: Franz Prochaska, 1884.

- Concerte, Componisten und Virtuosen der letzten fünfzehn Jahre, 1870–1885: Kritiken, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Literatur, 1886.

- “Die Musik in Wien,” in Die österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, vol. 1, Wien und Niederösterreich, ed. by crown prince archduke Rudolf, Vienna: Druck und Verlag der k. u. k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1886, 123–138.

- Musikalisches Skizzenbuch: Der “Modernen Oper” IV. Theil; Neue Kritiken und Schilderungen, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Litteratur, 1888.

- “Musik,” in Wien 1848–1888: Denkschrift zum 2. December 1888, ed. by the Vienna City Council, Vienna: Carl Konegen, 1888, 2:301–342.

- “Volksmusik, Dialect und Dialectpoesie,” in Die österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, vol. 2, Niederösterreich, ed. by crown prince archduke Rudolf, Vienna: Druck und Verlag der k. u. k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1888, 251–262 (in collaboration with Richard von Muth).

- Musikalisches und Litterarisches: Der “Modernen Oper” V. Theil; Kritiken und Schilderungen, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Litteratur, 1889.

- Aus dem Tagebuche eines Musikers: Der “Modernen Oper” VI. Theil; Kritiken und Schilderungen, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Litteratur, 1892.

- Aus meinem Leben, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Litteratur, 1894, vol. 1 and vol. 2.

- Fünf Jahre Musik, 1891–1895: Der “Modernen Oper” VII. Theil; Kritiken, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Litteratur, 1896.

- Am Ende des Jahrhunderts, 1895–1899: Der “Modernen Oper” VIII. Teil; Musikalische Kritiken und Schilderungen, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Litteratur, 1899.

- Aus neuer und neuerster Zeit: Der “Modernen Oper” IX. Teil; Musikalische Kritiken und Schilderungen, Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für deutsche Litteratur, 1900.

English-Language Translations of Hanslick’s Writings

- The Beautiful in Music: A Contribution to the Revisal of Musical Aesthetics, trans. by Gustav Cohen, London: Novello and Company, 1891.

- Vienna’s Golden Years of Music, 1850–1900, trans. by Henry Pleasants, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950.

- The Beautiful in Music: A Contribution to the Revisal of Musical Aesthetics, 2nd ed., trans. by Gustav Cohen, ed. by Morris Weitz, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Publishing, 1957.

- Eduard Hanslick: Music Criticisms 1846–1899, trans. by Henry Pleasants, London: Penguin Books, 1963.

- On the Musically Beautiful: A Contribution Towards the Revision of the Aesthetics of Music, trans. by Geoffrey Payzant, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1986.

- Hanslickʼs Music Criticisms, trans. by Henry Pleasants, New York: Dover Publications, 1988.

- “Eduard Hanslick: Brahms’s Newest Instrumental Compositions (1889),” trans. by Susan Gillespie, in Brahms and His World, ed. by Walter Frisch, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990, 145–150.

- “Eduard Hanslick: Memories and Letters,” trans. by Susan Gillespie, in Brahms and His World, ed. by Walter Frisch, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990, 163–184.

- “Hanslick contra Wagner: ‘The Ring Cycle Comes to Vienna’ and ‘Parsifal Literature,’” trans. by Thomas Grey, in Richard Wagner and His World, ed. by Thomas Grey, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009, 409–425.

- Eduard Hanslick’s ‘On the Musically Beautiful’: A New Translation, trans. by Lee Rothfarb and Christoph Landerer, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.